Types of genetic mutations: tiny changes, big impacts

Our genes are made of deoxyribonucleic acid (commonly known as DNA), that tell our cells how to function. When these sequences are altered, the effects can be dramatic. Small changes can have enormous consequences—especially when they occur in genes responsible for brain development, metabolism, or the immune system.

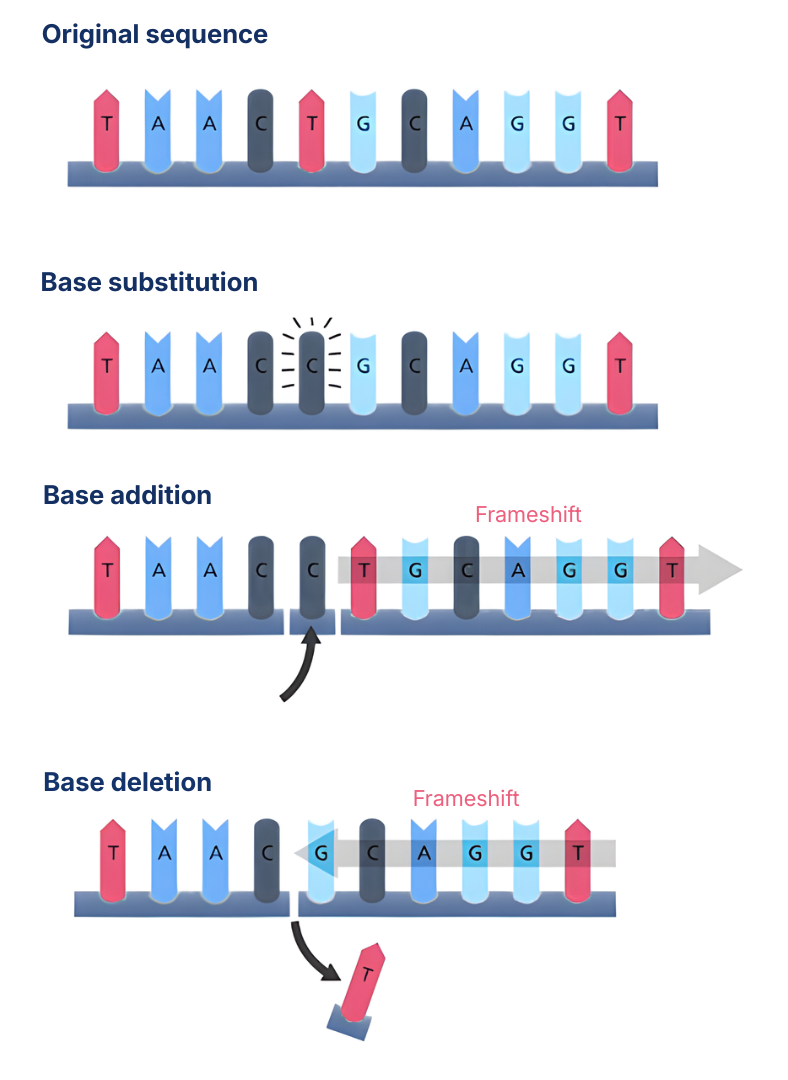

Point mutations

A single “letter” in the DNA is changed, which can stop a gene from making a functional protein. E.g.: Sickle cell disease.

Insertions/Deletions (indels)

Extra letters are added or removed, often causing a shift in how the gene is read. E.g.: Cystic fibrosis.

Copy number variations

Whole sections of DNA are duplicated or deleted, which may affect several genes at once.

Structural rearrangements

Pieces of chromosomes are inverted or swapped, disrupting normal gene function.

Gene regulation & epigenetics: More than just the code

Not all rare diseases are caused by mutations in genes themselves. Some are due to how genes are turned on or off—a field known as epigenetics.

DNA methylation

Adding chemical tags (methyl groups) to DNA can silence important genes. These modifications can prevent the proper expression of genes critical for normal development.

Histone modification

DNA is wrapped around proteins called histones; modifying them affects how tightly genes are packed and whether they can be read, influencing gene accessibility.

Non-coding RNAs

These molecules don't make proteins but help regulate gene activity by binding to DNA or other RNA molecules to control expression patterns.

Disruption in these regulatory mechanisms can lead to developmental syndromes or complex neurogenetic disorders. For example, Prader-Willi syndrome and Angelman syndrome are caused by epigenetic changes, not just DNA sequence mutations.

Genetic inheritance patterns: Passing it on

Understanding how rare diseases are inherited helps with diagnosis, family planning, and treatment decisions. Some rare diseases appear spontaneously due to new (de novo) mutations, meaning there’s no family history—making them harder to predict.

Autosomal recessive

Two copies of a mutated gene (one from each parent) are needed for the disease to manifest. Carriers typically show no symptoms. E.g.: Tay-Sachs disease.

Autosomal dominant

Just one mutated gene copy can cause the disease, affecting multiple generations. E.g.: Marfan syndrome.

X-linked

The mutation is on the X chromosome, often affecting males more severely as they have only one X chromosome. E.g.: Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Mitochondrial inheritance

Passed only from mothers through mitochondrial DNA found outside the cell nucleus. E.g.: Leigh syndrome.

Molecular causes: A starting point

Knowing the molecular cause of a disease is the first step toward finding a targeted treatment. Whether it’s replacing a faulty gene, modulating gene expression, or developing small molecules that fix protein function, every therapy begins with a solid understanding of the biology behind the disease.

As part of the ERDERA initiative, advancing genetic and molecular research is crucial to unlocking treatments for the 30 million Europeans living with a rare disease.

Future scientific developments will explore how these discoveries are transformed into diagnostics and therapies—paving the way for personalised medicine approaches that could revolutionise rare disease management.